Comparing two unpaired means#

Introduction#

In hypothesis testing, the unpaired t-test is a valuable tool for determining if two separate groups have truly different average values. Whether we’re investigating the impact of a new drug on blood pressure or comparing crop yields from two different fertilizers, the unpaired t-test helps us draw statistically sound conclusions from our data.

We use the unpaired t-test specifically when we have two independent groups or samples. These groups are not paired or matched in any way. For instance, we might have one group of patients receiving a new medication and another group receiving a placebo. The test assesses whether any observed difference in the means of these two groups is statistically significant or simply due to chance.

Before applying the unpaired t-test, it’s important to make sure our data meets certain assumptions:

Independence: the observations within each group should be independent of each other.

Normality: the data within each group should ideally follow a normal distribution. However, the t-test is reasonably robust to moderate deviations from normality, especially with larger sample sizes.

Equal variances: the variances of the two groups should be approximately equal. If the variances differ significantly, alternative versions of the t-test (such as Welch’s t-test) can be used.

The unpaired t-test works by calculating a test statistic that quantifies the difference between the means of the two groups relative to the variability within each group. This test statistic follows a known distribution (the t-distribution) under the null hypothesis of no difference between the group means. By comparing the calculated test statistic to the expected distribution, we obtain a P value. If the P value falls below our chosen significance level (alpha), we reject the null hypothesis and conclude that a statistically significant difference exists between the two group means.

In the following sections, we’ll delve deeper into the mathematical foundations of the unpaired t-test, explore its practical applications, and provide the knowledge needed to confidently apply this test in our own analyses.

Preparing data for hypothesis testing#

Descriptive statistics and visualization#

In this section, we will introduce the importance of descriptive statistics and visualization in understanding the characteristics of the two samples being compared. We will emphasize how these techniques provide valuable insights into the central tendency, spread, and distribution of the data, which are crucial for interpreting the results of the unpaired t-test.

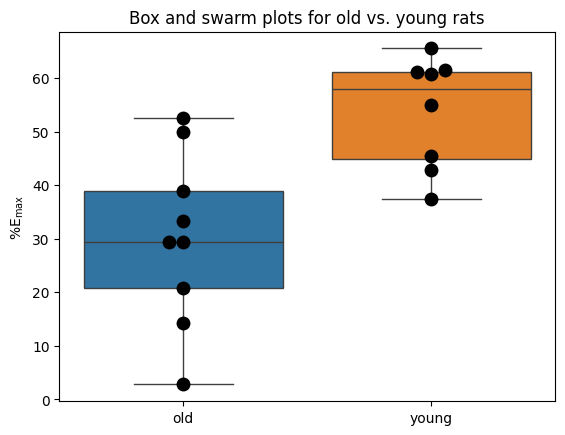

Frazier and colleagues investigated the impact of norepinephrine on bladder muscle relaxation in rats. Their study specifically examined the maximum relaxation (\(\%\text{E}_\text{max}\)) achievable with high doses of this neurotransmitter, comparing the responses of old (‘old’) and young (‘yng’) rats.

import numpy as np

# We use the data from Table 30.1 of the book Intuitive Biostatistics

old = np.array([20.8, 2.8, 50, 33.3, 29.4, 38.9, 29.4, 52.6, 14.3]) # old rats

yng = np.array([45.5, 55, 60.7, 61.5, 61.1, 65.5, 42.9, 37.5]) # young rats

import scipy.stats as stats

# Descriptive statistics

old_stats = stats.describe(old)

yng_stats = stats.describe(yng)

print("Descriptive statistics for 'old':\n", old_stats, '\n')

print("Descriptive statistics for 'young':\n", yng_stats)

Descriptive statistics for 'old':

DescribeResult(nobs=9, minmax=(2.8, 52.6), mean=30.16666666666667, variance=259.0375, skewness=-0.17569385392311104, kurtosis=-0.8080848898945967)

Descriptive statistics for 'young':

DescribeResult(nobs=8, minmax=(37.5, 65.5), mean=53.7125, variance=107.4069642857143, skewness=-0.4421628669270582, kurtosis=-1.3632352105713499)

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# Box and swarm plots

sns.boxplot(data=[old, yng])

sns.swarmplot(data=[old, yng], color='black', size=10)

plt.ylabel(r"$\%\text{E}_\text{max}$")

plt.xticks([0, 1], ['old', 'young'])

plt.title("Box and swarm plots for old vs. young rats");

Assessing assumptions#

Before proceeding with any hypothesis test, it’s crucial to verify that our data adheres to the underlying assumptions of the chosen statistical method. This subsection emphasizes the importance of checking for normality and homogeneity of variance, two common assumptions in many parametric tests, including the unpaired t-test. We’ll briefly discuss the methods used to assess these assumptions, such as normality tests and tests for equal variances, and outline the potential consequences of violating these assumptions. Additionally, we’ll highlight the available remedies or alternative approaches when assumptions are not met, ensuring the robustness and validity of our statistical inferences.

Normality testing#

One of the fundamental assumptions of the unpaired t-test is that the data within each group is approximately normally distributed. To assess this assumption, we employ normality tests such as the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus K² and Shapiro-Wilk tests, or visual inspections of histograms or Q-Q plots, as discussed in greater details in a previous chapter about normality test. These tests help us gauge whether the observed data aligns with the expected characteristics of a normal distribution.

# Normality tests

# D'Agostino-Pearson K² test

k2_old, pval_k2_old = stats.normaltest(old)

k2_yng, pval_k2_yng = stats.normaltest(yng)

print(

'old',

f"D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus: K2={k2_old:.2f}, P value={pval_k2_old:.3f}",

sep='\t')

print(

'young',

f"D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus: K2={k2_yng:.2f}, P value={pval_k2_yng:.3f}",

sep='\t')

# Shapiro-Wilk

shapiro_old, pval_shapiro_old = stats.shapiro(old)

shapiro_yng, pval_shapiro_yng = stats.shapiro(yng)

print(

'old',

f"Shapiro-Wilk's normality test P value={pval_shapiro_old:.3f}",

sep='\t')

print(

'young',

f"Shapiro-Wilk's normality test P value={pval_shapiro_yng:.3f}",

sep='\t')

# Interpret the results

alpha = 0.05 # Set the desired significance level

if (pval_k2_old > alpha and pval_k2_yng > alpha) \

or (pval_shapiro_old > alpha and pval_shapiro_yng > alpha):

print("\nBoth groups' data are not inconsistent with a normal distribution\n\

(failed to reject null hypothesis of normality)")

else:

print("\nAt least one group's data is not consistent with a normal distribution")

old D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus: K2=0.11, P value=0.947

young D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus: K2=1.75, P value=0.418

old Shapiro-Wilk's normality test P value=0.900

young Shapiro-Wilk's normality test P value=0.238

Both groups' data are not inconsistent with a normal distribution

(failed to reject null hypothesis of normality)

c:\Users\Sébastien\Documents\data_science\biostatistics\intuitive_biostatistics\.env\Lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\_axis_nan_policy.py:418: UserWarning: `kurtosistest` p-value may be inaccurate with fewer than 20 observations; only n=9 observations were given.

return hypotest_fun_in(*args, **kwds)

c:\Users\Sébastien\Documents\data_science\biostatistics\intuitive_biostatistics\.env\Lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\_axis_nan_policy.py:418: UserWarning: `kurtosistest` p-value may be inaccurate with fewer than 20 observations; only n=8 observations were given.

return hypotest_fun_in(*args, **kwds)

Pingouin’s normality function actually performs both the Shapiro-Wilk test and the D’Agostino-Pearson test.

import pingouin as pg

# Function to perform tests and print results

def normality_tests(data, sample_type):

s = f"{'Test':<20} {'W':<6} {'P value':<8} {'normal'}"

print(f"Normality tests for {sample_type}".center(len(s), "-"))

print(s)

# D'Agostino-Pearson Test

dagostino_results = pg.normality(data, method='normaltest')

print(f"{'D\'Agostino-Pearson':<20} {dagostino_results['W'][0]:<6.2f} \

{dagostino_results['pval'][0]:<8.3f} {dagostino_results['normal'][0]}")

# Shapiro-Wilk Test

shapiro_results = pg.normality(

data,

method='shapiro')

print(f"{'Shapiro-Wilk':<20} {shapiro_results['W'][0]:<6.2f} \

{shapiro_results['pval'][0]:<8.3f} {shapiro_results['normal'][0]}")

print("-" * len(s))

# Perform tests and print results

normality_tests(old, "old rats")

print('\n')

normality_tests(yng, "young rats")

--------Normality tests for old rats-------

Test W P value normal

D'Agostino-Pearson 0.11 0.947 True

Shapiro-Wilk 0.97 0.900 True

-------------------------------------------

-------Normality tests for young rats------

Test W P value normal

D'Agostino-Pearson 1.75 0.418 True

Shapiro-Wilk 0.89 0.238 True

-------------------------------------------

c:\Users\Sébastien\Documents\data_science\biostatistics\intuitive_biostatistics\.env\Lib\site-packages\scipy\stats\_axis_nan_policy.py:418: UserWarning: `kurtosistest` p-value may be inaccurate with fewer than 20 observations; only n=8 observations were given.

return hypotest_fun_in(*args, **kwds)

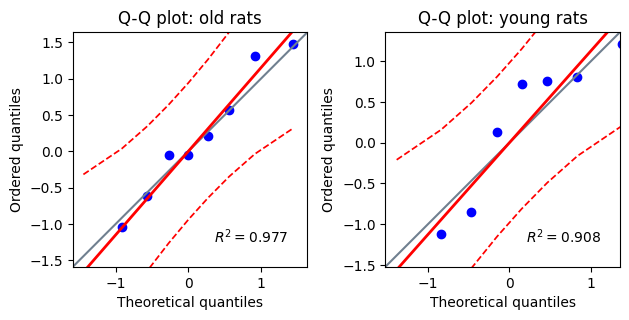

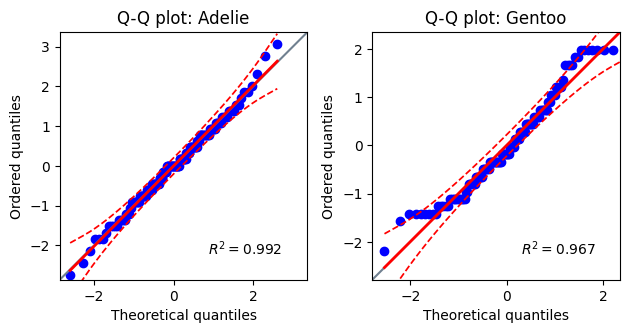

Additionally, the Pingouin library provides a convenient function for generating Q-Q plots, which offer a visual assessment of normality by comparing the observed data quantiles against the expected quantiles of a normal distribution.

# Plotting Q-Q plots

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2)

titles = ["Q-Q plot: old rats", "Q-Q plot: young rats"]

for i, (data, title) in enumerate(zip([old, yng], titles)):

pg.qqplot(

data,

dist='norm',

ax=axes[i],

confidence=0.95,)

axes[i].set_title(title)

plt.tight_layout() # Ensures plots don't overlap

While the unpaired t-test is reasonably robust to moderate deviations from normality, especially with larger sample sizes, severe violations can impact the accuracy of the test’s results. When the normality assumption is not met, the calculated P value may be unreliable, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions about the statistical significance of the difference between group means.

In such cases, we have a few options:

Transform the data: if the data exhibits a clear pattern of non-normality, we might attempt to transform it (e.g., using log transformations or square root transformations) to achieve a more normal distribution.

Use non-parametric alternatives: when transformations are ineffective or impractical, we can consider non-parametric tests like the Mann-Whitney U test, as discussed in the dedicated section, which do not rely on the normality assumption.

Proceed with caution: if the sample sizes are relatively large and the deviations from normality are not severe, we might proceed with the unpaired t-test, acknowledging the potential limitations in the interpretation of the results.

Homoscedasticity testing#

Another crucial assumption underlying the unpaired t-test is that the variances (or spreads) of the two groups being compared are approximately equal. This property is known as homoscedasticity. In this subsection, we’ll explore the importance of this assumption and introduce statistical tests, such as Levene’s test, that help us assess whether our data meets this criterion.

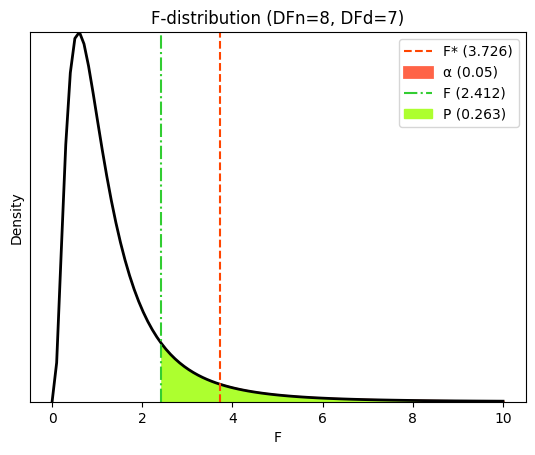

F-test of equality of variances#

The F-test, formally known as the F-test of equality of variances, is a statistical method used to compare the variances of two or more groups. In our context, it assesses whether the ‘old’ and ‘young’ groups have significantly different variances. The test calculates an F-statistic based on the ratio of the group variances and their respective sample sizes. This F-statistic is then compared to an F-distribution to obtain a P value.

# Calculate sample variances s (unbiased estimator)

var_old = np.var(old, ddof=1)

var_yng = np.var(yng, ddof=1)

# Calculate the ratio of variances

var_ratio = var_old / var_yng

# Sample sizes

n_old = len(old)

n_yng = len(yng)

# Degrees of freedom

df_old = n_old - 1

df_yng = n_yng - 1

# Calculate the F-statistic

f_statistic = max(var_ratio, 1/var_ratio) # ensures that the F-statistic >= 1

# Calculate the p-value using the F-distribution (two-sided test)

p_value_fstat = 2 * (1 - stats.f.cdf(f_statistic, df_old, df_yng))

# Print the results

print(f"Variance ratio (old/young) = {var_ratio:.3f}")

print(f"F-statistic = {f_statistic:.3f}")

print(f"P value for the F-test of equal variance (manual calculation) = {p_value_fstat:.4f}")

Variance ratio (old/young) = 2.412

F-statistic = 2.412

P value for the F-test of equal variance (manual calculation) = 0.2631

Assuming the null hypothesis of equal variances is true, there is a 26.31% probability that we would observe a discrepancy between the sample standard deviations as large as (or larger than) the one we found, purely due to random sampling. Let’s visualize the F-statistic (F), critical F-value (F*), and the area (P value) under the F distribution corresponding to our dataset.

# Significance level (alpha)

α = 0.05

# Calculate critical value

f_crit = stats.f.ppf(1 - α, df_old, df_yng)

# Generate x values for plotting

x = np.linspace(0, 10, 100)

hx = stats.f.pdf(x, df_old, df_yng)

# Create the plot

plt.plot(x, hx, lw=2, color="black")

# Plot the critical value

plt.axvline(

x=f_crit, # type: ignore

color='orangered',

linestyle='--',

label=f'F* ({f_crit:.3f})')

# Shade the probability alpha

plt.fill_between(

x[x >= f_crit],

hx[x >= f_crit],

linestyle="-",

linewidth=2,

color='tomato',

label=f'α ({α})')

# Plot the observed F-statistic

plt.axvline(

x=f_statistic, # type: ignore

color='limegreen',

linestyle='-.',

label=f'F ({f_statistic:.3f})')

# Shade the P value area

plt.fill_between(

x[x >= f_statistic],

hx[x >= f_statistic],

color='greenyellow',

label=f'P ({p_value_fstat:.3f})')

# Add labels and title

plt.xlabel('F')

plt.ylabel('Density')

plt.margins(x=0.05, y=0)

plt.yticks([])

plt.title(f"F-distribution (DFn={df_old}, DFd={df_yng})")

plt.legend();

In the context of homoscedasticity tests like Levene’s test or Bartlett’s test, the null hypothesis states that the variances are equal.

Therefore:

High P value: we fail to reject the null hypothesis, meaning we do not have enough evidence to say the variances are different. This suggests that the assumption of equal variances is reasonable.

Low P value: we reject the null hypothesis, meaning we have evidence to suggest the variances are not equal. This indicates that the assumption of equal variances is violated.

Levene and Bartlett tests#

We’ll now leverage the convenience and robustness of Levene’s and Bartlett’s tests to evaluate the assumption of equal variances. A deeper dive into the manual F-statistic calculation will come later when we cover ANOVA.

Levene’s test assesses the equality of variances across groups by analyzing the spread of the absolute deviations from a central measure (typically the median) within each group. The test statistic calculated in Levene’s test approximately follows an F-distribution under the null hypothesis of equal variances. This allows us to compute a P value to determine the statistical significance of any observed differences in variances.

Bartlett’s test also evaluates the homogeneity of variances across groups, but it operates under the assumption that the data within each group is normally distributed. The test statistic in Bartlett’s test approximately follows a chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of groups minus one, again enabling us to obtain a P value for hypothesis testing.

While both tests serve the same purpose, Levene’s test is generally considered more robust to deviations from normality compared to Bartlett’s test. Therefore, if we suspect or have evidence that the data might not be perfectly normally distributed, Levene’s test is often the preferred choice. On the other hand, if we’re confident about the normality of the data, Bartlett’s test can be a suitable option.

# Using scipy.stats

# Levene's test for equal variances

levene_statistic, levene_p_value = stats.levene(old, yng)

# Bartlett's test for equal variances

bartlett_statistic, bartlett_p_value = stats.bartlett(old, yng)

# Print the results

print(f"Levene's test statistic = {levene_statistic:.3f}, \

P value = {levene_p_value:.4f}")

print(f"Bartlett's test statistic = {bartlett_statistic:.3f}, \

P value = {bartlett_p_value:.4f}")

Levene's test statistic = 0.686, P value = 0.4204

Bartlett's test statistic = 1.290, P value = 0.2560

# Using pingouin

# Levene's test for equal variances

levene_results = pg.homoscedasticity([old, yng], method='levene')

# Bartlett's test for equal variances

bartlett_results = pg.homoscedasticity([old, yng], method='bartlett')

# Print the results

print("Levene and Bartlett's test results:")

print(levene_results)

print(bartlett_results)

Levene and Bartlett's test results:

W pval equal_var

levene 0.686405 0.420378 True

T pval equal_var

bartlett 1.290011 0.256046 True

A small P value, indicating a potential violation of the equal variances assumption, presents a nuanced situation. While some fields, including certain areas of biology, might tolerate minor deviations from homoscedasticity, it’s generally advisable to adopt a more conservative approach. Consider using Welch’s t-test, which is designed to handle unequal variances, or explore data transformations that might improve the homogeneity of variances. In cases of severe non-normality or highly unequal variances, especially with small sample sizes, consider using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test as a robust alternative to Welch’s t-test, or a bootstrap approach, both discussed at the end of this chapter.

Assessing the significance of mean differences with t-test#

The central question in many research studies is whether an intervention, treatment, or characteristic leads to a meaningful difference between groups. In this section, we’ll explore how the unpaired t-test helps us answer this question by comparing the means of two independent samples.

mean_diff = np.mean(yng) - np.mean(old)

print(f"Mean difference between old and young rats = {mean_diff:.3f}")

Mean difference between old and young rats = 23.546

The t-ratio#

At the core of the unpaired t-test lies the t-ratio, also named t-value, or t-score, and abbreviated t, a pivotal statistic that quantifies the disparity between the means of two groups relative to their combined variability. The t-ratio used in the unpaired t-test shares a structural resemblance to the t-statistic we encountered earlier when constructing confidence intervals for a single mean in a previous chapter. Both involve a ratio of a difference to a measure of variability and follow a t-distribution. However, the t-ratio in the unpaired t-test focuses on comparing two sample means, while the t-statistic for confidence intervals is used to estimate a single population mean.

In this subsection, we’ll delve into the mathematical underpinnings of the t-ratio, exploring how it incorporates sample means, variances, and sample sizes to provide a standardized measure of the difference between groups. Understanding the t-ratio is crucial for interpreting the results of the unpaired t-test and drawing meaningful conclusions about the statistical significance of any observed differences.

Welch’s t-test#

Manual calculation of the Welch’s t-ratio#

In the general case, where we do not assume equal variances, the t-ratio for the unpaired t-test is often referred to as Welch’s t-statistic. This test utilizes the following t-statistic:

where \(\bar x_1\) and \(\bar x_2\) are the sample means, \(s_1^2\) and \(s_2^2\) are the sample variances of the two groups, and \(n_1\) and \(n_2\) are the sample sizes. Remember the relationships between variance \(s^2\), standard deviation \(s\), and standard error of the mean: \(s_{\overline{x}} = s / \sqrt{n}\).

The standard error of the difference between the means with “unequal variances”, denoted by \(s_{\bar x_1 - \bar x_2}\), is calculated as the square root of the sum of the estimated variances of the two sample means:

This standard error accounts for the variability within each group and is used in the denominator of Welch’s t-statistic:

The degrees of freedom for this t-statistic are approximated using the Welch-Satterthwaite equation, which can be further simplified using standard errors:

# Calculate the standard error for unequal variances (Welch's t-test)

# The variances were already calculated for the F-test

se_unequal = np.sqrt(var_old / n_old + var_yng / n_yng)

# Calculate Welch's t-statistic

t_statistic_welch = mean_diff / se_unequal

# Calculate the degrees of freedom using the Welch-Satterthwaite equation

df_welch = se_unequal**4 / ((var_old/n_old)**2/(n_old-1) + (var_yng/n_yng)**2/(n_yng-1))

# se^2 = s/n --> se^4 = (s/n)^2

# Or using the intermediate formula

#df_welch = se_unequal**4 / (((var_old/n_old)** 2)/(n_old-1) + ((var_yng/n_yng)** 2)/(n_yng-1))

# Print the results

print(f"t-statistic (Welch's) = {t_statistic_welch:.4f} with {df_welch:.3f} \

degrees of freedom (Welch-Satterthwaite approximation)")

t-statistic (Welch's) = 3.6242 with 13.778 degrees of freedom (Welch-Satterthwaite approximation)

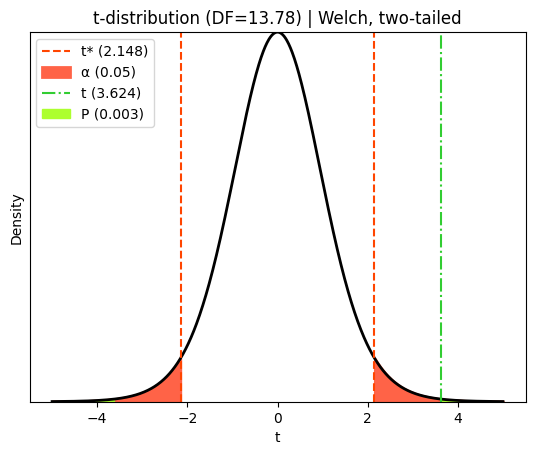

Welch’s P value#

Now that we have our t-statistic and degrees of freedom, we can determine the P value associated with our test. The P value will quantify the probability of observing a t-statistic as extreme as (or more extreme than) the one we calculated, assuming the null hypothesis of no difference between the group means is true. We will utilize the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the t-distribution to compute this probability.

# Calculate the P value using the t-distribution (two-sided test)

p_value_welch = 2 * (1 - stats.t.cdf(abs(t_statistic_welch), df_welch))

# Print the results

print(f"P value for Welch's t-test = {p_value_welch:.5f}")

P value for Welch's t-test = 0.00283

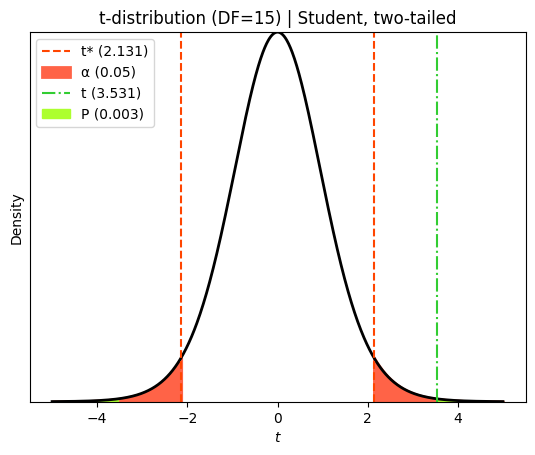

Visualizing Welch’s values#

To gain a deeper understanding of the results of Welch’s t-test, let’s visualize the t-statistic, the critical t-values that define the rejection regions, and the areas under the t-distribution corresponding to the P value. This visual representation will help us grasp the statistical significance of the observed difference between the group means and the role of the degrees of freedom in shaping the t-distribution.

# Significance level (alpha)

α = 0.05

# Calculate critical t-values (two-tailed test)

t_crit_lower_welch = stats.t.ppf(α/2, df_welch)

t_crit_upper_welch = stats.t.ppf(1 - α/2, df_welch)

# Generate x values for plotting

x = np.linspace(-5, 5, 1000)

hx = stats.t.pdf(x, df_welch)

# Create the plot

plt.plot(x, hx, lw=2, color="black")

# Plot the critical t-values

plt.axvline(

x=t_crit_upper_welch, # type: ignore

color='orangered',

linestyle='--',

label=f't* ({t_crit_upper_welch:.3f})')

plt.axvline(

x=t_crit_lower_welch, # type: ignore

color='orangered',

linestyle='--',)

# Shade the rejection regions (alpha)

plt.fill_between(

x[x <= t_crit_lower_welch],

hx[x <= t_crit_lower_welch],

linestyle="-",

linewidth=2,

color='tomato',

label=f'α ({α})')

plt.fill_between(

x[x >= t_crit_upper_welch],

hx[x >= t_crit_upper_welch],

linestyle="-",

linewidth=2,

color='tomato')

# Plot the observed t-statistic

plt.axvline(

x=t_statistic_welch,

color='limegreen',

linestyle='-.',

label=f't ({t_statistic_welch:.3f})')

# Shade the P-value areas (two-tailed)

plt.fill_between(

x[x <= -abs(t_statistic_welch)],

hx[x <= -abs(t_statistic_welch)],

color='greenyellow',

label=fr'P ({p_value_welch:.3f})',)

plt.fill_between(

x[x >= abs(t_statistic_welch)],

hx[x >= abs(t_statistic_welch)],

color='greenyellow')

# Add labels and title

plt.xlabel('t')

plt.ylabel('Density')

plt.margins(x=0.05, y=0)

plt.yticks([])

plt.title(f"t-distribution (DF={df_welch:.2f}) | Welch, two-tailed")

plt.legend();

The red dashed lines in this diagram represent the critical t-values that define the rejection regions for a two-tailed t-test at a 5% significance level. The ‘tails’ of the curve outside these lines each represent 2.5% of the probability distribution under the null hypothesis (that the true population mean difference is zero).

The green dot-dashed line represents the observed t-statistic calculated from our sample data. The P value corresponds to the total probability of observing a t-statistic as extreme as (or more extreme than) the one we calculated, assuming the null hypothesis is true. In a two-tailed test like this, we consider both tails of the distribution because the true population mean difference could be either higher or lower than zero. One-tailed tests (as shown later) are used when we have a directional hypothesis, specifically testing if the difference is ‘less than zero’ or ‘greater than zero’.

Welch’s confidence interval#

A confidence interval provides a range of plausible values for the true difference in population means when comparing two unpaired groups using the Welch test. It gives us an idea of the precision of our estimate of this difference.

To calculate this confidence interval, we need to consider the variability within each group, acknowledging that these variances may not be equal. Here’s how it’s done:

Calculate the point estimate: this is the difference between the sample means of the two groups as \(\bar X_1 - \bar X_2\)

Calculate the standard error: the standard error of the difference in means for the Welch test is calculated as \(s_{\bar x_1 - \bar x_2} = \sqrt{s_1^2 / n_1 + s_2^2 / n_2}\), where \(s_1\) and \(s_2\) are the sample standard deviations of the two groups, and \(n_1\) and \(n_2\) are the respective sample sizes

Determine the degrees of freedom: the degrees of freedom for the Welch test are calculated using a rather complex formula (Welch-Satterthwaite equation) to account for the unequal variances

Find the critical t-value: using the desired confidence level (e.g., 95%) and the calculated degrees of freedom, find the corresponding critical t-value from the t-distribution table or using statistical software

Calculate the margin of error: multiply the standard error by the critical t-value: \(W = t^\ast \times s_{\bar x_1 - \bar x_2}\)

Construct the confidence interval: subtract and add the margin of error to the point estimate to obtain the lower and upper bounds of the confidence interval: \((\bar X_1 - \bar X_2) \pm W\), where \(W\) is the margin of error

# Calculate the confidence interval (e.g., 95% confidence)

confidence_level = 0.95

margin_of_error_welch = abs(stats.t.ppf((1 + confidence_level) / 2, df_welch)) * se_unequal

ci_welch = (mean_diff - margin_of_error_welch, mean_diff + margin_of_error_welch)

# Print the results

print(f"Mean difference (young - old) = {mean_diff:.3f}")

print(f"95% confidence interval for the mean difference: \

[{ci_welch[0]:.3f}, {ci_welch[1]:.3f}]")

Mean difference (young - old) = 23.546

95% confidence interval for the mean difference: [9.591, 37.501]

Performing the Welch’s t-test in Python#

Let’ts conduct Welch’s t-test using both the SciPy and Pingouin libraries in Python. We’ll compare their implementations and outputs, highlighting their respective advantages.

# Welch's t-test using SciPy

t_statistic_scipy_welch, p_value_scipy_welch = stats.ttest_ind(yng, old, equal_var=False)

# Welch's t-test using Pingouin

ttest_results_pingouin_welch = pg.ttest(yng, old, correction=True) # type: ignore

# Print the results

print("Welch's t-test results (SciPy):")

print(f"t-statistic = {t_statistic_scipy_welch:.3f}, \

P value = {p_value_scipy_welch:.4f}")

print("\nWelch's t-test results (Pingouin):")

ttest_results_pingouin_welch

Welch's t-test results (SciPy):

t-statistic = 3.624, P value = 0.0028

Welch's t-test results (Pingouin):

| T | dof | alternative | p-val | CI95% | cohen-d | BF10 | power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-test | 3.624246 | 13.777968 | two-sided | 0.002828 | [9.59, 37.5] | 1.715995 | 14.51 | 0.909532 |

The Welch’s t-test yielded a t-statistic of 3.624 with an associated P value of 0.003. This P value is less than the commonly used significance level of 0.05, indicating strong evidence to reject the null hypothesis of no difference between the means of the old and young groups of rats. Therefore, we conclude that there is a statistically significant difference in the \(\%\text{E}_\text{max}\) between the two groups.

Furthermore, the 95% confidence interval for the mean difference (young - old) is [9.591, 37.501]. This suggests that we can be 95% confident that the true population mean difference lies within this range. The fact that this interval does not include zero further supports the conclusion that the two groups are significantly different.

Student t-test#

While Welch’s t-test offers a robust approach for comparing means when variances might be unequal, there are scenarios where we have reason to believe that the variances of the two groups are approximately the same. In such cases, we can employ the standard unpaired t-test, also known as Student’s t-test. This test relies on the assumption of equal variances, leading to a slightly simpler formula for the t-statistic and a different calculation for the degrees of freedom.

Student’s t-ratio formula#

Starting from the general formula of the t-ratio, and under the assumption of equal variance where \(s_1^2 = s_2^2 = s_p^2\), the t-ratio for the unpaired t-test assuming equal variances is calculated as follows:

where \(\bar x_1\) and \(\bar x_2\) are the sample means, \(n_1\) and \(n_2\) are the sample sizes, and \(s_p^2\) is pooled sample variance \(s_p^2\) calculated as:

where \(s_1^2\) and \(s_2^2\) are the sample variances of the two groups. Even if we assume equal variances, we still need to combine the information from both samples to get a more precise estimate of the common variance.

In the Student’s t-test, the standard error of the difference between the means is calculated using the pooled variance as:

This standard error, which incorporates the pooled estimate of the common variance, is used in the denominator of the t-statistic for the Student’s t-test:

The degrees of freedom for the Student’s t-test (assuming equal variances) are \(\mathrm{DF} = n_1 + n_2 - 2\), which directly corresponds to the denominator in the pooled variance formula. This reflects the fact that the pooled variance estimate combines information from both samples, each contributing its degrees of freedom to the final estimate.

# Degrees of freedom for equal variances t-test

df_student = n_old + n_yng - 2

# Calculate pooled variance using the sample variances determined in the previous section

pooled_var = ((n_old-1)*var_old + (n_yng-1)*var_yng) / df_student

# Calculate the pooled standard error

se_pooled = np.sqrt(pooled_var * (1/n_old + 1/n_yng))

# Calculate the Student's t-statistic

t_statistic_student = mean_diff / se_pooled

# Print the results

print(f"t-statistic (Student) = {t_statistic_student:.4f} with \

{df_student} degrees of freedom")

t-statistic (Student) = 3.5315 with 15 degrees of freedom

Special case of equal variances and sample sizes#

In the situation where \(n_1 = n_2 = n\), and \(s_1^2 = s_2^2 = s^2\), with \(n\) the common sample size and \(s^2\) the common sample variance:

Therefore

and \(\mathrm{DF} = 2n -2\).

Student’s P value#

Having calculated the t-statistic and degrees of freedom, we can now determine the P value. Similar to Welch’s t-test, we’ll use the t-distribution’s CDF to compute the P value, which quantifies the probability of observing such an extreme t-statistic (or more extreme) if the null hypothesis were true.

# Calculate the P value using the t-distribution (two-sided test)

p_value_student = 2 * (1 - stats.t.cdf(abs(t_statistic_student), df_student))

# Print the results

print(f"P value for the Student's t-test = {p_value_student:.5f}")

P value for the Student's t-test = 0.00302

Visualizing Student’s values#

To better understand the results of the Student’s t-test, let’s visualize the t-statistic, critical t-values, and the P value areas under the t-distribution. This visual representation will aid in understanding the statistical significance of the observed mean difference and the impact of degrees of freedom on the t-distribution’s shape.

# Calculate critical t-values (two-tailed test)

t_crit_lower_student = stats.t.ppf(alpha/2, df_student)

t_crit_upper_student = stats.t.ppf(1 - alpha/2, df_student)

# Generate x values for plotting

x = np.linspace(-5, 5, 1000)

hx = stats.t.pdf(x, df_student)

# Create the plot

plt.plot(x, hx, lw=2, color="black")

# Plot the critical t-values

plt.axvline(

x=t_crit_lower_student, # type: ignore

color='orangered',

linestyle='--',)

plt.axvline(

x=t_crit_upper_student, # type: ignore

color='orangered',

linestyle='--',

label=f't* ({t_crit_upper_student:.3f})')

# Shade the rejection regions (alpha)

plt.fill_between(

x[x <= t_crit_lower_student],

hx[x <= t_crit_lower_student],

linestyle="-",

linewidth=2,

color='tomato',

label=f'α ({alpha})')

plt.fill_between(

x[x >= t_crit_upper_student],

hx[x >= t_crit_upper_student],

linestyle="-",

linewidth=2,

color='tomato')

# Plot the observed t-statistic

plt.axvline(

x=t_statistic_student,

color='limegreen',

linestyle='-.',

label=f't ({t_statistic_student:.3f})')

# Shade the P-value areas (two-tailed)

plt.fill_between(

x[x <= -abs(t_statistic_student)],

hx[x <= -abs(t_statistic_student)],

color='greenyellow',

label=f'P ({p_value_student:.3f})',)

plt.fill_between(

x[x >= abs(t_statistic_student)],

hx[x >= abs(t_statistic_student)],

color='greenyellow')

# Add labels and title

plt.xlabel(r'$t$')

plt.ylabel('Density')

plt.margins(x=0.05, y=0)

plt.yticks([])

plt.title(f"t-distribution (DF={df_student}) | Student, two-tailed")

plt.legend();

Student’s confidence interval#

The confidence interval for the Student’s t-test follows a similar process as the Welch test, with a key difference in calculating the standard error and degrees of freedom.

Instead of using separate variances for each group, the Student’s t-test assumes equal variances and pools the variance from both groups to estimate a common variance. This pooled variance is then used to calculate the standard error of the difference in means.

Not to forget that the degrees of freedom for the Student’s t-test are simpler to calculate, as they are based on the total sample size of both groups minus 2.

With these adjustments to the standard error and degrees of freedom, the remaining steps to construct the confidence interval are the same as those described for the Welch test.

# Calculate the confidence interval (e.g., 95% confidence)

margin_of_error_student = abs(stats.t.ppf((1 + confidence_level) / 2, df_student)) * se_pooled

ci_student = (mean_diff - margin_of_error_student, mean_diff + margin_of_error_student)

# Print the results

print(f"Mean difference (young - old) = {mean_diff:.3f}")

print(f"95% confidence interval for the mean difference: \

[{ci_student[0]:.3f}, {ci_student[1]:.3f}]")

Mean difference (young - old) = 23.546

95% confidence interval for the mean difference: [9.335, 37.757]

Performing the Student’s t-test in Python#

We can readily perform the Student’s t-test using either scipy.stats or Pingouin. The implementation is nearly identical to Welch’s t-test, with the key difference being that we change the equal_var (in SciPy) or correction (in Pingouin) parameter to explicitly indicate the assumption of equal variances.

# Student's t-test using SciPy (assuming equal variances)

t_statistic_scipy_student, p_value_scipy_student = stats.ttest_ind(yng, old, equal_var=True)

# Student's t-test using Pingouin (assuming equal variances)

ttest_results_pingouin_student = pg.ttest(yng, old, correction=False) # type: ignore

# Print the results

print("Student's t-test results (SciPy):")

print(f"t-statistic = {t_statistic_scipy_student:.3f}, \

P value = {p_value_scipy_student:.4f}")

print("\nStudent's t-test results (Pingouin):")

ttest_results_pingouin_student

Student's t-test results (SciPy):

t-statistic = 3.531, P value = 0.0030

Student's t-test results (Pingouin):

| T | dof | alternative | p-val | CI95% | cohen-d | BF10 | power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-test | 3.531488 | 15 | two-sided | 0.003022 | [9.33, 37.76] | 1.715995 | 12.56 | 0.909532 |

Similar to the Welch’s t-test, the Student’s t-test also revealed a statistically significant difference between the two groups. The calculated t-statistic was 3.531, with an associated P value of 0.003. This P value falls below the conventional significance level of 0.05, providing strong evidence to reject the null hypothesis of no difference in the mean \(\%\text{E}_\text{max}\) between the ‘old’ and ‘young’ groups.

The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference (young - old) is [9.335, 37.757]. This interval suggests we can be 95% confident that the true population mean difference in \(\%\text{E}_\text{max}\) lies within this range. The absence of zero within this interval further reinforces the conclusion of a significant difference between the two groups.

Effect size#

Cohen’s d is a widely used effect size measure for unpaired t-tests. It essentially standardizes the difference between the two group means by dividing it by a measure of variability:

However, since we’re dealing with two independent groups, the calculation of the standard deviation (\(s\)) used in the denominator differs slightly depending on whether we assume equal variances or not, as we saw in the Welch and Student t-tests.

# Calculate the standard deviations from the standard errors

sd_unequal = se_unequal * np.sqrt((n_yng * n_old) / (n_yng + n_old)) # For Welch's t-test

sd_pooled = se_pooled * np.sqrt(n_yng + n_old - 2) # For Student's t-test

# Calculate Cohen's d manually

cohens_d_manual_welch = mean_diff / sd_unequal

cohens_d_manual_student = mean_diff / sd_pooled

print(f"Cohen's d (manual, Welch's): {cohens_d_manual_welch:.3f}")

print(f"Cohen's d (manual, Student's): {cohens_d_manual_student:.3f}")

Cohen's d (manual, Welch's): 1.761

Cohen's d (manual, Student's): 0.912

To calculate effect size in various scenarios, including unpaired tests, we can utilize the compute_effsize function provided by the Pingouin library.

# Calculate unbiased Cohen's d using pingouin

effect_size_pingouin = pg.compute_effsize(yng, old, eftype='cohen')

print(f"Unbiased Cohen's d (pingouin): {effect_size_pingouin:.3f}")

Unbiased Cohen's d (pingouin): 1.716

The interpretation guidelines for Cohen’s d in unpaired t-tests are generally the same as those for paired t-tests (discussed in the next chapter):

Small effect: d ≈ 0.2

Medium effect: d ≈ 0.5

Large effect: d ≈ 0.8

Effect size in unpaired t-tests helps understand the practical significance of the findings. A statistically significant result (small P value) doesn’t necessarily mean the effect is large or meaningful. Conversely, a non-significant result might still indicate a meaningful effect, especially if the study has low power due to a small sample size. By considering both the P value and the effect size, we can gain a more complete picture of your results and draw more informed conclusions.

Working with real world data#

Loading the data#

Let’s introduce the Palmer penguins dataset from the Pingouin library and demonstrate how to perform an unpaired t-test directly on its columns. We’ll also explore one-sided t-tests and investigate the relationship between overlapping error bars and the statistical significance of mean differences.

import pandas as pd

# List all available datasets in pingouin (commented out)

# pg.list_dataset()

# Load the 'penguins' dataset

penguins = pg.read_dataset('penguins')

# Display the first 5 rows of the dataset

penguins.head()

| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Adelie | Biscoe | 37.8 | 18.3 | 174.0 | 3400.0 | female |

| 1 | Adelie | Biscoe | 37.7 | 18.7 | 180.0 | 3600.0 | male |

| 2 | Adelie | Biscoe | 35.9 | 19.2 | 189.0 | 3800.0 | female |

| 3 | Adelie | Biscoe | 38.2 | 18.1 | 185.0 | 3950.0 | male |

| 4 | Adelie | Biscoe | 38.8 | 17.2 | 180.0 | 3800.0 | male |

Understanding the data#

Let’s print some descriptive statistics for the different variables.

# Display descriptive statistics

penguins.describe(include='all')

| species | island | bill_length_mm | bill_depth_mm | flipper_length_mm | body_mass_g | sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 344 | 344 | 342.000000 | 342.000000 | 342.000000 | 342.000000 | 333 |

| unique | 3 | 3 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 2 |

| top | Adelie | Biscoe | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | male |

| freq | 152 | 168 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN | 168 |

| mean | NaN | NaN | 43.921930 | 17.151170 | 200.915205 | 4201.754386 | NaN |

| std | NaN | NaN | 5.459584 | 1.974793 | 14.061714 | 801.954536 | NaN |

| min | NaN | NaN | 32.100000 | 13.100000 | 172.000000 | 2700.000000 | NaN |

| 25% | NaN | NaN | 39.225000 | 15.600000 | 190.000000 | 3550.000000 | NaN |

| 50% | NaN | NaN | 44.450000 | 17.300000 | 197.000000 | 4050.000000 | NaN |

| 75% | NaN | NaN | 48.500000 | 18.700000 | 213.000000 | 4750.000000 | NaN |

| max | NaN | NaN | 59.600000 | 21.500000 | 231.000000 | 6300.000000 | NaN |

The culmen is the upper ridge of a bird’s bill. In the simplified penguins data, culmen length and depth are renamed as variables ‘bill_length_mm’ and ‘bill_depth_mm’ to be more intuitive.

For this penguin data, the culmen (bill) length and depth are measured as shown below:

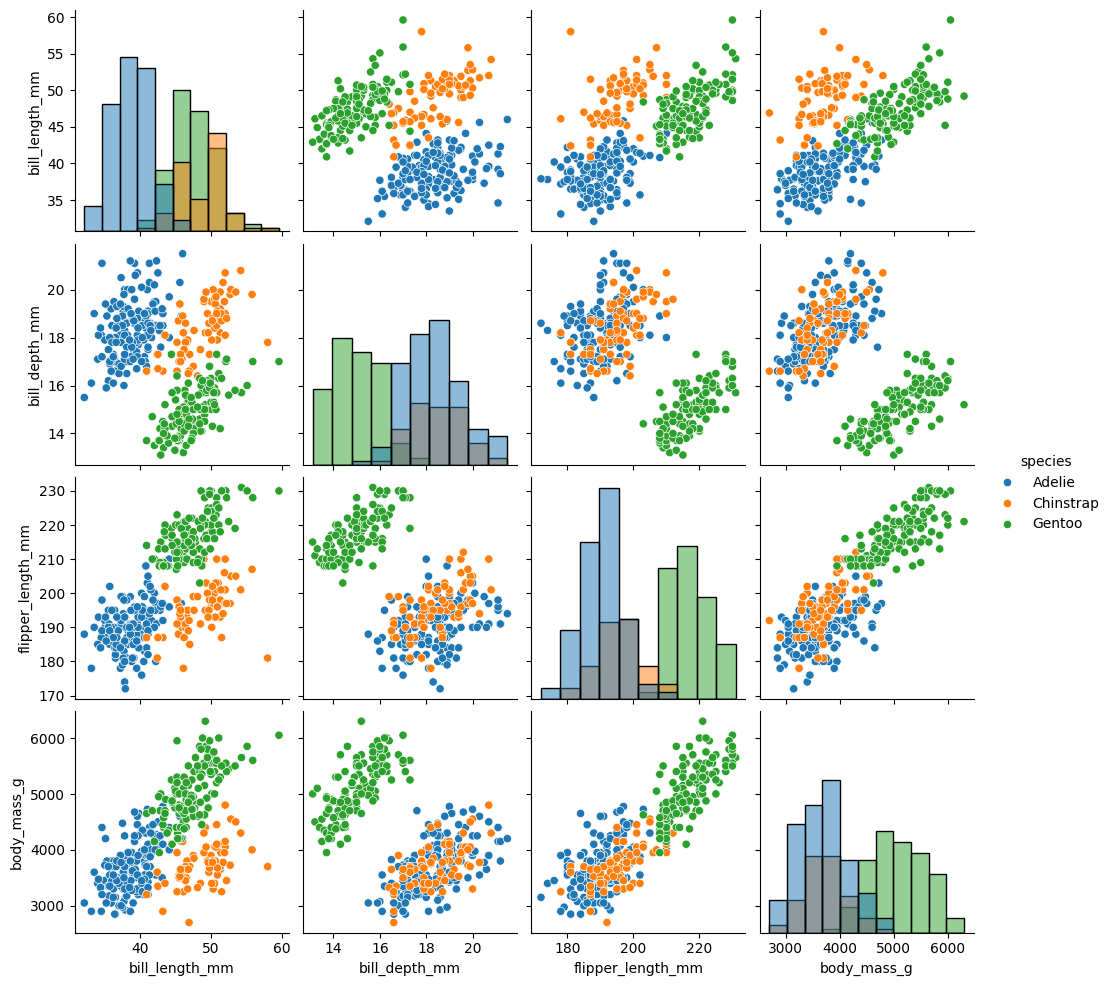

Let’s now create a grid of scatterplots that visualize the relationships between pairs of numerical variables in the penguins DataFrame. It also incorporates color-coded distinctions based on the ‘species’ column and customizes the diagonal plots to display histograms, providing insights into the individual distributions of each variable for each species.

sns.pairplot(penguins, hue="species", diag_kind="hist");

Checking assumptions#

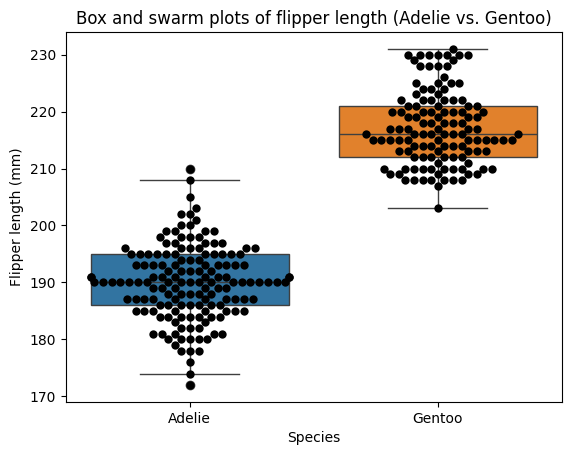

Flipper length appears to be a promising variable for distinguishing between penguin species. Let’s apply the t-test framework we’ve established to investigate this further. To illustrate the concepts clearly, we’ll focus on the two most populous species in the dataset: Adelie and Gentoo. However, it’s important to note that in a comprehensive analysis, we would ideally include all groups and employ ANOVA (which we’ll discuss in a later chapter) to account for potential differences among all species simultaneously.

# Statistics for groups of species

penguins.groupby(by='species')['flipper_length_mm'].describe()

| count | mean | std | min | 25% | 50% | 75% | max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| species | ||||||||

| Adelie | 151.0 | 189.953642 | 6.539457 | 172.0 | 186.0 | 190.0 | 195.0 | 210.0 |

| Chinstrap | 68.0 | 195.823529 | 7.131894 | 178.0 | 191.0 | 196.0 | 201.0 | 212.0 |

| Gentoo | 123.0 | 217.186992 | 6.484976 | 203.0 | 212.0 | 216.0 | 221.0 | 231.0 |

# Remove the Chinstrap species

# Create a copy to avoid modifying the original DataFrame

penguins_filtered = penguins[penguins['species'] != 'Chinstrap'].copy()

# Box and swarm plots

sns.boxplot(

data=penguins_filtered,

x='species',

y='flipper_length_mm',

hue='species')

sns.swarmplot(

data=penguins_filtered,

x='species',

y='flipper_length_mm',

color='black',

size=6)

plt.xlabel('Species')

plt.ylabel('Flipper length (mm)')

plt.title("Box and swarm plots of flipper length (Adelie vs. Gentoo)");

# Perform tests using our own function (see normality testing)

normality_tests(

adelie_flipper:=penguins_filtered.loc[

penguins_filtered['species'] == 'Adelie', 'flipper_length_mm'].values,

"Adelie penguins")

print('\n')

normality_tests(

gentoo_flipper:=penguins_filtered.loc[

penguins_filtered['species'] == 'Gentoo', 'flipper_length_mm'].values,

"Gentoo penguins")

----Normality tests for Adelie penguins----

Test W P value normal

D'Agostino-Pearson 1.08 0.582 True

Shapiro-Wilk 0.99 0.720 True

-------------------------------------------

----Normality tests for Gentoo penguins----

Test W P value normal

D'Agostino-Pearson 6.12 0.047 False

Shapiro-Wilk 0.96 0.002 False

-------------------------------------------

# Plotting Q-Q plots

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2)

titles = ["Q-Q plot: Adelie", "Q-Q plot: Gentoo"]

for i, (data, title) in enumerate(zip([adelie_flipper, gentoo_flipper], titles)):

pg.qqplot(

data,

dist='norm',

ax=axes[i],

confidence=0.95,)

axes[i].set_title(title)

plt.tight_layout() # Ensures plots don't overlap

# Levene's test for equal variances

# Note the difference with the method call on a DataFrame compared to arrays

pg.homoscedasticity(

data=penguins_filtered,

dv='flipper_length_mm',

group='species',

method='levene')

| W | pval | equal_var | |

|---|---|---|---|

| levene | NaN | NaN | False |

The problem of missing values#

The Levene’s test returned NaN values and equal_var=False. This discrepancy is unexpected, given the similar standard deviations and sample sizes observed in the descriptive statistics. It’s likely that missing values are causing Levene’s test to fail, as many statistical tests struggle to handle NaN values. Let’s investigate whether the adelie_flipper or gentoo_flipper arrays contain any missing data.

penguins_filtered.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

Index: 276 entries, 0 to 343

Data columns (total 7 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 species 276 non-null object

1 island 276 non-null object

2 bill_length_mm 274 non-null float64

3 bill_depth_mm 274 non-null float64

4 flipper_length_mm 274 non-null float64

5 body_mass_g 274 non-null float64

6 sex 265 non-null object

dtypes: float64(4), object(3)

memory usage: 17.2+ KB

As there are some missing non-null values in the dataset, and in the ‘flipper_length_mm’ columns in particular, we’ll need to decide how to handle them, e.g., remove rows with missing values, or impute missing values, before running the test again. Let’s drop the rows containing missing values in the ‘flipper_length_mm’ column.

penguins_filtered_clean = penguins_filtered.dropna(subset='flipper_length_mm')

pg.homoscedasticity(

data=penguins_filtered_clean,

dv='flipper_length_mm',

group='species',

method='levene')

| W | pval | equal_var | |

|---|---|---|---|

| levene | 0.157042 | 0.692205 | True |

Performing t-test#

While the flipper length data for Adelie penguins appears to be normally distributed, the Gentoo flipper lengths show some deviation from normality, particularly at the extremes. However, given the relatively large sample sizes (n=151 for Adelie and n=123 for Gentoo), we can proceed with the Student’s t-test (assuming equal variances), acknowledging the potential limitations due to this minor departure from normality. Though, the most appropriate statistical test would be to compare all the groups using ANOVA (discussed in a future chapter).

# Perform Student t-test

pg.ttest(

x=adelie_flipper, # the method removes missing values by default

y=gentoo_flipper,

correction=False # type: ignore

)

| T | dof | alternative | p-val | CI95% | cohen-d | BF10 | power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-test | -34.414958 | 272 | two-sided | 4.211309e-101 | [-28.79, -25.68] | 4.18005 | 1.128e+97 | 1.0 |

The extremely small P value (4.211e-101) is far below the typical significance level of 0.05. This provides overwhelming evidence to reject the null hypothesis of no difference between the two group means.

The 95% confidence interval [-28.79, -25.68] provides a range of plausible values for the true difference between the population means. The fact that this interval doesn’t include zero further supports the conclusion of a significant difference.

Therefore, we can conclude that there is a statistically significant difference between the means of the two groups being compared.

Overlapping distributions#

In the previous example with flipper length, we observed that non-overlapping distributions generally corresponded to a statistically significant difference in means. However, it’s important to remember that overlapping distributions do not necessarily imply the absence of a significant difference. The statistical significance of the mean difference depends on various factors, including the degree of overlap, sample sizes, and the variability within each group.

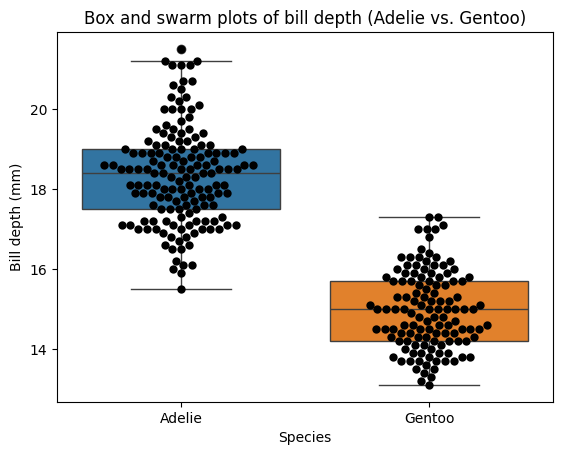

Let’s examine the ‘bill_depth_mm’ variable for Adelie and Gentoo penguins.

# Box and swarm plots

sns.boxplot(

data=penguins_filtered,

x='species',

y='bill_depth_mm',

hue='species')

sns.swarmplot(

data=penguins_filtered,

x='species',

y='bill_depth_mm',

color='black',

size=6)

plt.xlabel('Species')

plt.ylabel('Bill depth (mm)')

plt.title("Box and swarm plots of bill depth (Adelie vs. Gentoo)");

# Perform Student t-test

pg.ttest(

x=penguins_filtered.loc[penguins_filtered['species'] == 'Adelie', 'bill_depth_mm'],

y=penguins_filtered.loc[penguins_filtered['species'] == 'Gentoo', 'bill_depth_mm'],

correction=False # type: ignore

)

| T | dof | alternative | p-val | CI95% | cohen-d | BF10 | power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-test | 24.792495 | 272 | two-sided | 9.311098e-72 | [3.1, 3.63] | 3.011303 | 8.109e+67 | 1.0 |

Furthermore, overlapping error bars do not necessarily imply that the means of the populations are not significantly different. The degree of overlap, the sample sizes, and the variability within each group all play a role in determining statistical significance. It’s always crucial to conduct formal hypothesis tests, like the t-test, to draw valid conclusions about differences between groups.

This observation is particularly relevant when dealing with distributions based on low sample sizes, as their error bars tend to be wider, leading to more overlap even when there might be a true difference in population means. It’s essential to rely on the P value from the t-test rather than solely on visual inspection of error bar overlap, especially when sample sizes are small.

We can use the following rules of thumbs:

Type of error bar |

Overlapping error bars |

Non-overlapping error bars |

|---|---|---|

SD |

No conclusion |

No conclusion |

SEM |

Likely P > 0.05 |

No conclusion |

95% CI |

No conclusion |

Likely P < 0.05 |

One-sided t-test#

In our penguin dataset scenario, we aim to determine if the bill depth of Adelie penguins, after subtracting 3 mm, is still significantly greater than the bill depth of Gentoo penguins. Mathematically, we want to test if: \(\bar x_\text{Adelie} - 3 > \bar x_\text{Gentoo}\). We can restate \(\bar x_{\text{Adelie} - 3} > \bar x_\text{Gentoo}\). This allows us to frame our hypotheses for a one-sided t-test:

Null hypothesis (H0): the mean bill depth of Adelie penguins, minus 3 mm, is equal to or less than the mean bill depth of Gentoo penguins (\(\bar x_\text{Adelie - 3} \le \bar x_\text{Gentoo}\)).

Alternative hypothesis (H1): the mean bill depth of Adelie penguins, minus 3 mm, is greater than the mean bill depth of Gentoo penguins.

Let’s conduct a one-sided t-test on our sample data to evaluate these hypotheses.

# Perform one-sided Student t-test with pingouin

pg.ttest(

x=penguins_filtered.loc[penguins_filtered['species'] == 'Adelie', 'bill_depth_mm'] - 3,

# Missing values are automatically removed from the data in pingouin

y=penguins_filtered.loc[penguins_filtered['species'] == 'Gentoo', 'bill_depth_mm'],

correction=False, # type: ignore

alternative='greater',

)

| T | dof | alternative | p-val | CI95% | cohen-d | BF10 | power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-test | 2.684262 | 272 | greater | 0.003858 | [0.14, inf] | 0.326031 | 7.951 | 0.849133 |

# Perform one-sided Student t-test with scipy.stats

stats.ttest_ind(

penguins_filtered.loc[penguins_filtered['species'] == 'Adelie', 'bill_depth_mm'] - 3,

penguins_filtered.loc[penguins_filtered['species'] == 'Gentoo', 'bill_depth_mm'],

equal_var=True,

alternative='greater',

nan_policy='omit', # scipy doesn't remove missing values automatically

)

TtestResult(statistic=2.684262207738359, pvalue=0.003857530781549446, df=272.0)

# Finally statsmodels also offers a comprehensive t-test API

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Perform Student's t-test

ttest_results_sm = sm.stats.ttest_ind(

x1=penguins_filtered_clean.loc[penguins_filtered['species'] == 'Adelie', 'bill_depth_mm'],

# statsmodels doesn't support policy for missing values

x2=penguins_filtered_clean.loc[penguins_filtered['species'] == 'Gentoo', 'bill_depth_mm'],

usevar='pooled', # Specify equal variances assumption

alternative='larger', # Test if the Adelie bill depth mean (x1) is larger

value=3 # difference between the means (x1 - x2) under the null hypothesis

)

# Extract and print the relevant statistics

t_statistic_sm = ttest_results_sm[0]

p_value_sm = ttest_results_sm[1]

df_sm = ttest_results_sm[2]

print(f"Student's t-test results:")

print(f"t-statistic = {t_statistic_sm:.3f}, P value = {p_value_sm:.5f}, DF= {df_sm}")

Student's t-test results:

t-statistic = 2.684, P value = 0.00386, DF= 272.0

Non-parametric methods#

While biological data rarely perfectly adhere to a Gaussian (normal) distribution, many biological variables exhibit an approximately bell-shaped distribution. Parametric tests, such as the t-test and ANOVA, are often robust to minor deviations from normality, especially with large samples. Consequently, these tests are widely used across various scientific disciplines.

Non-parametric methods offer a valuable set of tools for analyzing data when the assumptions of parametric tests, such as the t-test or ANOVA, are not met. Unlike parametric methods that assume the data are sampled from a Gaussian distribution, non-parametric methods do not rely on such strict distributional assumptions. Instead, many of these tests operate by ranking the data from low to high and analyzing these ranks, making them less sensitive (more robust) to outliers and deviations from normality. But when the data is truly Gaussian (normally distributed), non-parametric tests generally have lower statistical power compared to their parametric counterparts. This means they might be less likely to detect a true difference if one exists.

The choice between parametric and non-parametric tests can also be influenced by the sample size:

Distribution |

Test |

Small samples |

Large Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

Gaussian |

Non-parametric |

Misleading, low power |

Nearly as powerful as parametric tests |

Non-Gaussian |

Parametric |

Misleading, not robust |

Robust to mild deviations from normality |

Moreover, reporting confidence intervals for non-parametric tests can be more challenging, and they might not be as readily available or interpretable as those for parametric tests, and extending non-parametric tests to more complex models, such as regression models, can be less straightforward compared to parametric methods.

Below is a flowchart designed to help choosing which functions of Pingouin are adequate for a non-parametric analysis:

Of note, computer-intensive methods like bootstrapping and permutation tests also fall under the non-parametric umbrella, as they don’t assume a specific distribution for the data. These methods provide robust alternatives for estimating P values and confidence intervals, especially when dealing with small sample sizes or non-normal data, and will be discussed in the next section.

Performing the Mann-Whitney U test manually#

Exact method#

The Mann-Whitney U test (also known as the Wilcoxon rank-sum test) is a non-parametric method for comparing two unpaired groups. It assesses whether one group tends to have larger or smaller values than the other. Unlike the t-test, it doesn’t assume that the data follows a normal distribution.

If we have two groups with observations \(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_m\) and \(y_1, y_2, \dots, y_n\) sampled from populations \(X\) and \(Y\), respectively, the Mann-Whitney U/Wilcoxon rank-sum test assesses the null hypothesis that the probability of a randomly selected observation from group \(X\) being greater than a randomly selected observation from group \(Y\) is \(0.5\). Formally:

Under the null hypothesis, \(P(x_i > y_j) = 0.5\), the probability that a randomly selected observation from one group is larger than a randomly selected observation from the other group is equal to 0.5. Essentially, this means the two groups have the same distribution.

Under the alternative hypothesis, \(P(x_i > y_j) \ne 0.5\), the probability that a randomly selected observation from one group is larger than a randomly selected observation from the other group is not equal to 0.5, implying that the two groups have different distributions.

How do the test works concretely:

Combine and rank: combine the data from both groups and rank the values from lowest to highest, ignoring the group labels

Calculate rank sums: calculate the sum of the ranks for each group. We assign the median rank to tied values (mid-rank method)

Calculate \(U\) statistic: the U statistic is calculated for each group based on the rank sums, sample sizes, and a correction factor for ties (if any). Specifically, the formulas for the U statistics are:

\(U_x = mn + \frac{m(m+1)}{2} - R_x\)

\(U_y = mn + \frac{n(n+1)}{2} - R_y\)

where \(m\) is the number of samples drawn from population \(X\), \(n\) is the number of samples drawn from population \(Y\), and \(R_x\) and \(R_y\) are the sum of the ranks attributed to population \(X\) and \(Y\), respectively.

The final \(U\) statistic used for the test is the minimum of the two: \(U = \min(U_x, U_y)\)

Determine significance: \(U\) is compared to a critical value from a Mann-Whitney U table (for the chosen significance level and sample sizes). If the calculated \(U\) value is less than or equal to the critical value (\(U \leq U^\ast\)), we reject the null hypothesis. Otherwise, we fail to reject the null hypothesis.

from scipy.stats import rankdata

# Combine the data

combined_data = np.concatenate((old, yng))

# Rank the data

ranks = rankdata(combined_data)

# 'average' method used to assign ranks to tied elements by default

# Separate the ranks for each group

old_ranks = ranks[:len(old)]

yng_ranks = ranks[len(old):]

# Calculate the rank sums

R1 = np.sum(old_ranks)

R2 = np.sum(yng_ranks)

# Calculate the U statistic for each group

n1 = len(old)

n2 = len(yng)

U1 = n1 * n2 + (n1 * (n1 + 1)) / 2 - R1

U2 = n1 * n2 + (n2 * (n2 + 1)) / 2 - R2

# Determine the U statistic

U_statistic = min(U1, U2)

# Critical U value for n1=9 and n2=8 with alpha=0.05 from the table

# https://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/mph-modules/bs/bs704_nonparametric/Mann-Whitney-Table-CriticalValues.pdf

U_critical = 15

# Print the results

print(f"U1 = {U1:n}")

print(f"U2 = {U2:n}")

print(f"U = {U_statistic:n}")

print(f"U* (n={n1}, m={n2}, alpha=0.05) = {U_critical:n}")

# Compare U to the critical value and draw a conclusion

if U_statistic <= U_critical:

print("Reject the null hypothesis. There is a significant difference between the groups.")

else:

print("Fail to reject the null hypothesis. There is no significant difference between the groups.")

U1 = 65

U2 = 7

U = 7

U* (n=9, m=8, alpha=0.05) = 15

Reject the null hypothesis. There is a significant difference between the groups.

The Mann-Whitney U test’s critical values table is generated from the probability distribution of the U statistic, as detailed in the original paper by Mann and Whitney. They used a recursion relation to define this distribution:

Python readily supports recursive functions, providing a concise and elegant way to implement algorithms that involve repeated self-reference.

def mann_whitney_u_prob(U, n, m):

"""

Calculate the probability of a specific U value in the Mann-Whitney U distribution.

Args:

U: The U statistic value.

n: The number of observations in the first group.

m: The number of observations in the second group.

Returns:

The probability of the U value.

"""

if n == 0 or m == 0:

return 1 if U == 0 else 0

elif n > 0 and m > 0:

return (n * mann_whitney_u_prob(U - m, n - 1, m) + m * mann_whitney_u_prob(U, n, m - 1)) / (n + m)

else:

return 0 # Handle invalid input (negative n or m)

# Using the current data

probability = mann_whitney_u_prob(U_statistic, n1, n2)

print(f"P(U={U_statistic}, n={n1}, m={n2}) = {probability:.4f}")

P(U=7.0, n=9, m=8) = 0.0006

To gain a deeper understanding of the underlying probability distribution of the U statistic, let’s generate a table that illustrates the exact probabilities for various combinations of sample size \(m\) and \(U\) values, with \(n\) fixed. This table will provide insights into the behavior of the U statistic under different scenarios and help us appreciate the complexities involved in calculating the exact P values for the Mann-Whitney U test.

# Generate the table for n = 9

n = n1

U_values = range(10) # U from 0 to 9

m_values = range(1, 10) # m from 1 to 9

table_data = {}

for m in m_values:

row_data = {}

for U in U_values:

row_data[U] = mann_whitney_u_prob(U, n, m)

table_data[m] = row_data

df = pd.DataFrame(table_data)

df.columns.name="m"

df.index.name="U"

# Display the table

pg.print_table(df, floatfmt='.6f')

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

-------- -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- --------

0.100000 0.018182 0.004545 0.001399 0.000500 0.000200 0.000087 0.000041 0.000021

0.100000 0.018182 0.004545 0.001399 0.000500 0.000200 0.000087 0.000041 0.000021

0.100000 0.036364 0.009091 0.002797 0.000999 0.000400 0.000175 0.000082 0.000041

0.100000 0.036364 0.013636 0.004196 0.001499 0.000599 0.000262 0.000123 0.000062

0.100000 0.054545 0.018182 0.006993 0.002498 0.000999 0.000437 0.000206 0.000103

0.100000 0.054545 0.022727 0.008392 0.003497 0.001399 0.000612 0.000288 0.000144

0.100000 0.072727 0.031818 0.012587 0.004995 0.002198 0.000962 0.000452 0.000226

0.100000 0.072727 0.036364 0.015385 0.006494 0.002797 0.001311 0.000617 0.000309

0.100000 0.090909 0.045455 0.020979 0.008991 0.003996 0.001836 0.000905 0.000452

0.100000 0.090909 0.054545 0.025175 0.011489 0.005195 0.002448 0.001193 0.000617

The P value represents the probability of observing a U value as extreme as, or more extreme than, the one calculated from the data, assuming the null hypothesis is true. The cumulative distribution function (CDF) provides this information: by summing the probabilities in all the rows above a cell in a given column in the U table, we are effectively calculating the probability of obtaining a U value less than or equal to the value represented by that cell. This cumulative probability is then used to determine the P value for the test. Below is the cumulative distribution table derived from the previous table.

# Calculate the cumulative sum of probabilities along the rows (axis=0)

df.cumsum(axis=0)

| m | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U | |||||||||

| 0 | 0.1 | 0.018182 | 0.004545 | 0.001399 | 0.000500 | 0.000200 | 0.000087 | 0.000041 | 0.000021 |

| 1 | 0.2 | 0.036364 | 0.009091 | 0.002797 | 0.000999 | 0.000400 | 0.000175 | 0.000082 | 0.000041 |

| 2 | 0.3 | 0.072727 | 0.018182 | 0.005594 | 0.001998 | 0.000799 | 0.000350 | 0.000165 | 0.000082 |

| 3 | 0.4 | 0.109091 | 0.031818 | 0.009790 | 0.003497 | 0.001399 | 0.000612 | 0.000288 | 0.000144 |

| 4 | 0.5 | 0.163636 | 0.050000 | 0.016783 | 0.005994 | 0.002398 | 0.001049 | 0.000494 | 0.000247 |

| 5 | 0.6 | 0.218182 | 0.072727 | 0.025175 | 0.009491 | 0.003796 | 0.001661 | 0.000782 | 0.000391 |

| 6 | 0.7 | 0.290909 | 0.104545 | 0.037762 | 0.014486 | 0.005994 | 0.002622 | 0.001234 | 0.000617 |

| 7 | 0.8 | 0.363636 | 0.140909 | 0.053147 | 0.020979 | 0.008791 | 0.003934 | 0.001851 | 0.000926 |

| 8 | 0.9 | 0.454545 | 0.186364 | 0.074126 | 0.029970 | 0.012787 | 0.005769 | 0.002756 | 0.001378 |

| 9 | 1.0 | 0.545455 | 0.240909 | 0.099301 | 0.041459 | 0.017982 | 0.008217 | 0.003949 | 0.001995 |

For instance, if the calculated U statistic is 7, and the corresponding probability for n = 9 and m = 8 is 0.00185, which is less than 0.05/2 = 0.025 (for a two-sided test), we reject the null hypothesis. This indicates a significant difference in the medians of the two groups.

# Display the cumulative probability for U=7 and m=8 (n=9)

cumulative_prob = df.cumsum(axis=0).loc[7, 8].item() # type: ignore

p_value = 2 * cumulative_prob # Multiply by 2 for two-tailed test

print(f"Cumulative probability for U=7 and m=8 (n=9): {cumulative_prob:.5f}")

print(f"P value (two-tailed): {p_value:.7f}")

# Compare the p-value to 0.05

if p_value < 0.05:

print("Reject the null hypothesis. There is a significant difference between the groups.")

else:

print("Fail to reject the null hypothesis. There is no significant difference between the groups.")

Cumulative probability for U=7 and m=8 (n=9): 0.00185

P value (two-tailed): 0.0037022

Reject the null hypothesis. There is a significant difference between the groups.

One practical advantage of non-parametric tests is their ability to handle data that contains values that are too high or too low to be precisely measured. In such cases, where exact quantification is impossible, we can assign arbitrary very low or very high values to these data points. Since non-parametric tests focus on the relative ranks of the data rather than their precise magnitudes, the test results won’t be affected by the lack of exact values for these extreme measurements.

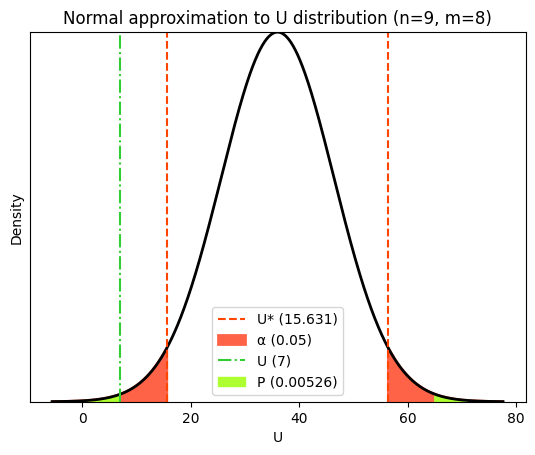

Asymptotic approach#

While statistical packages offer accurate calculations for the Mann-Whitney U test, visualizing its exact distribution can be complex. As an alternative, we can explore the asymptotic distribution (normal approximation) for visualization purposes. Keep in mind that this approximation might not be ideal for small samples, but it effectively illustrates the distribution’s shape and how the P value is computed.

In fact, for larger sample sizes, the distribution of the U statistic under the null hypothesis can be approximated by a normal distribution. This approximation simplifies the calculation of P values and makes it easier to visualize the distribution.

To define this approximate normal distribution, we need to know its mean and standard deviation. These parameters are calculated based on the sample sizes of the two groups being compared. The mean of the normal approximation is used to center the distribution curve on the plot. This helps in visually comparing the observed U statistic to the expected distribution under the null hypothesis. The mean and standard deviation are also used in the calculation of the z-score, which is then used to determine the P value based on the standard normal distribution.

from scipy.stats import norm

# Determine the meean and SD to approximate the distribution

μ = n1 * n2 / 2

σ = np.sqrt(n1 * n2 * (n1 + n2 + 1) / 12) # Based on the variance of rank sum

# Generate x values for plotting the normal distribution

x = np.linspace(μ - 4 * σ, μ + 4 * σ, 1000)

normal_pdf = norm.pdf(x, loc=μ, scale=σ)

# Create the plot

plt.plot(x, normal_pdf, lw=2, color="black")

# Plot the critical U-values (two-tailed test)

U_crit_lower = μ - norm.ppf(1 - alpha/2) * σ

U_crit_upper = μ + norm.ppf(1 - alpha/2) * σ

# Calculate the z-score

z_score = (U_statistic - μ) / σ

# Calculate the p-value (two-tailed)

p_value_U = 2 * (1 - norm.cdf(abs(z_score)))

plt.axvline(

x=U_crit_lower,

color='orangered',

linestyle='--')

plt.axvline(

x=U_crit_upper,

color='orangered',

linestyle='--',

label=f"U* ({U_crit_lower:.3f})")

# Shade the rejection regions (alpha)

plt.fill_between(

x,

normal_pdf,

where=(x <= U_crit_lower) | (x >= U_crit_upper),

linestyle="-",

linewidth=2,

color='tomato',

label=f'α ({alpha})')

# Plot the observed U-statistic

plt.axvline(

x=float(U_statistic),

color='limegreen',

linestyle='-.',

label=f'U ({U_statistic:n})')

# Shade the P-value areas (two-tailed)

plt.fill_between(

x,

normal_pdf,

where=(x <= U_statistic) | (x >= μ + (μ - U_statistic)),

color='greenyellow',

label=f"P ({p_value_U:.5f})")

# Add labels and title

plt.xlabel('U')

plt.ylabel('Density')

plt.margins(x=0.05, y=0)

plt.yticks([])

plt.title(f"Normal approximation to U distribution (n={n1}, m={n2})")

plt.legend();

Python tools for non-parametric unpaired t-test#

Python offers convenient and powerful tools for performing the Mann-Whitney U test, simplifying the analysis and providing additional functionalities.

SciPy provides a comprehensive collection of statistical functions, including the mannwhitneyu function for performing the Mann-Whitney U test.

from scipy.stats import mannwhitneyu

# Perform Mann-Whitney U test with exact p-value calculation

U_statistic_exact, p_value_exact = mannwhitneyu(old, yng, method='exact')

# Perform Mann-Whitney U test with asymptotic (normal approximation) p-value calculation

U_statistic_asymptotic, p_value_asymptotic = mannwhitneyu(old, yng, method='asymptotic', use_continuity=False)

# method='auto' choose between the 'asymptotic' and 'exact' based on the sample sizes and the presence of ties

# Print the results

print("Mann-Whitney U test results:")

print(f"Exact P value: {p_value_exact:.5f}")

print(f"Asymptotic P value: {p_value_asymptotic:.5f}")

Mann-Whitney U test results:

Exact P value: 0.00370

Asymptotic P value: 0.00523

Pingouin’s mwu function provides a more comprehensive output, including additional statistics like the rank biserial correlation and the common language effect size. These statistics offer further insights into the magnitude and direction of the difference between the two groups, complementing the P value obtained from the test, but won’t be disscussed here.

pg.mwu(old, yng, method='asymptotic', use_continuity=False, alternative='two-sided')

| U-val | alternative | p-val | RBC | CLES | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWU | 7.0 | two-sided | 0.005234 | -0.805556 | 0.097222 |

When the P value is less than 0.05 in a two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, using both exact and asymptotic methods, we can conclude that there is a significant difference between the two groups being compared. This means that the probability of observing the data (or more extreme data) if the null hypothesis were true is less than 5%. Therefore, we reject the null hypothesis, and conclude that there is a difference in the distribution between the two groups.

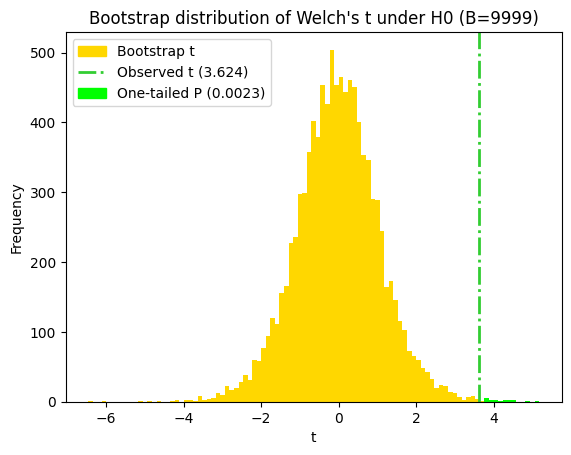

Bootstrapping and permutation tests#

Bootstrapping offers a powerful alternative for statistical inference, allowing us to estimate parameters and confidence intervals directly from the data itself, without relying on strong assumptions about the underlying population distribution. This approach, also known as non-parametric inference, was previously encountered in the chapter on calculating the confidence interval of a mean (univariate).

While bootstrapping is primarily used for estimation, permutation tests, another resampling-based method, are specifically designed for hypothesis testing. They can be employed to test various hypotheses, such as the null hypothesis of exchangeability (where group labels are irrelevant) or the hypothesis of equal means after shifting the group means to a common value.

The essence of bootstrapping#

The core idea behind bootstrapping is to treat our observed sample as miniature representation of the population. We repeatedly resample from our original sample to create multiple bootstrap samples. Each replicate is generated by randomly sampling (with replacement) from the original data, creating a new dataset of the same size.

The power of bootstrapping lies in its ability to empirically estimate the sampling distribution of a statistic of interest, such as the difference between group means. By calculating this statistic for each bootstrap sample, we generate a bootstrap distribution. This distribution serves as an approximation of how the statistic would vary if we were to repeatedly sample from the population. It’s important to note that while the central limit theorem guarantees that the distribution of sample means approaches a normal distribution as the sample size increases, with \(\bar X \sim \mathcal N(\mu, \frac{\sigma^2}{\sqrt{n}})\), bootstrapping doesn’t rely on this assumption. It directly leverages the empirical distribution of the data to make inferences. Learn more on bootstrap and computer-intensive methods in Wilcox (2010) and Manly and Navarro Alberto (2020).

For now, let’s return to the example of bladder muscle relaxation in old and young rats, where we have relatively small sample sizes. This scenario provides an excellent opportunity to showcase the power and utility of bootstrapping and permutation tests in handling such data limitations.

# Set random seed for reproducibility

np.random.seed(111)

# Generate 10,000 bootstrap replicates of the mean for each group

# !Make sure to choose exactly N elements randomly **with replacement**

n_replicates = 10000

bs_old_means = np.array([

np.mean(

np.random.choice(

old,

size=len(old),

replace=True

)) for _ in range(n_replicates)

])

bs_yng_means = np.array([

np.mean(np.random.choice(yng, size=len(yng), replace=True)) for _ in range(n_replicates)

])

# Calculate the difference between the bootstrap means for each replicate

# (cast operation on numpy arrays)

bs_mean_diff = bs_yng_means - bs_old_means

print(bs_mean_diff[:10]) # print the 10 first replicates

[25.07916667 23.89166667 22.01944444 29.45277778 23.34027778 26.37083333

22.95277778 19.46666667 27.01388889 27.89444444]

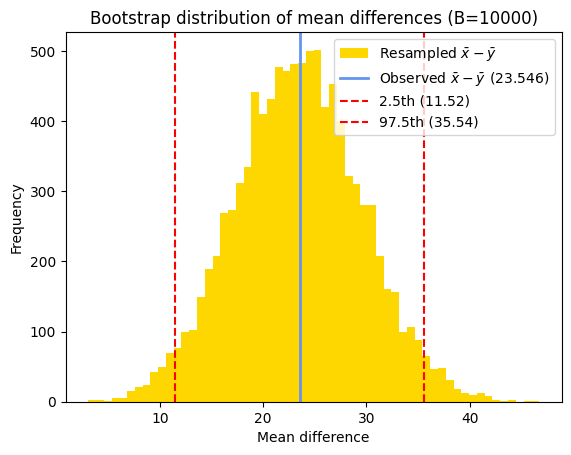

Estimate of the confidence interval#

Once we have the bootstrap distribution, we can estimate the confidence interval by finding the percentiles corresponding to the desired confidence level.

For a 95% confidence interval, we typically use the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bootstrap distribution. This means that 95% of the bootstrap estimates fall within this interval, providing a range of plausible values for the true population parameter. And as seen in the chapter about the confidence interval of a mean, i.e., the confidence interval of the distribution of an unique sample, we can determine the bootstrap standard error as the standard deviation of the bootstrapped distribution of the mean difference.

# Calculate the 95% CI using np.percentile and the standard error

bs_m = np.mean(bs_mean_diff)

bs_CI = np.round(np.percentile(bs_mean_diff, [2.5, 97.5]), 2)

bs_s = np.std(bs_mean_diff, ddof=1)

# Print the results

print(f"Bootstrap estimate of the mean difference = {bs_m:5.2f}")

print(f"95% bootstrap percentile CI = {bs_CI}")

print(f"Bootstrap standard error = {bs_s:.5f}")

Bootstrap estimate of the mean difference = 23.44

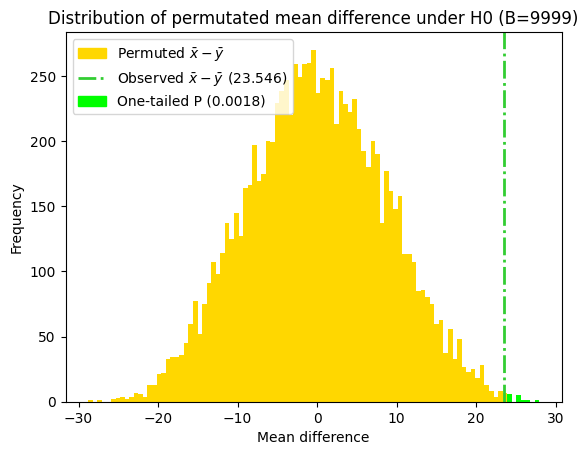

95% bootstrap percentile CI = [11.52 35.54]